In the frame

Graphic narratives are growing in a space where artists can communicate perspectives that may not find impetus in the mainstream, Vidyun Sabhaney, who has co-edited First Hand, tells Gargi Gupta

Few people outside Kerala today remember 'Nawab' Rajendran, the journalist and anti-corruption crusader who died in 2003. There's a Wikipedia entry on him but those are just dull details. But The Nawab, a graphic biography by Gokul Gopalakrishnan, fills the vacuum by bringing to life Rajendran's unworldly, sage-like mien and his uncompromising courage.

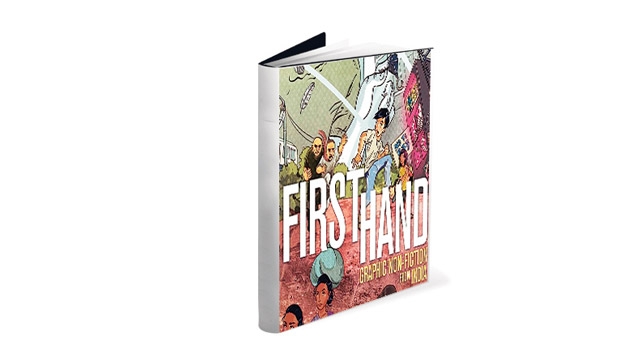

The Nawab is part of First Hand, a collection of 22 short non-fiction comic narratives that tell "urgent stories of the odds against which lives are being lived, and the events and forces that are shaping them", says Vidyun Sabhaney – who edited it along with Orijit Sen – in an interview.

How did this book come about? Would you describe the process of putting it together?

The idea for First Hand came almost two years ago. Comics have always been used to tell real experiences, incidents and ideas and place them within a larger context – whether journalistic, historical, stories of individual and collective struggle and hope, narratives of traumatic incidents, or larger social and political ideas. The comics medium is an ideal medium to do this – it allows you to move very quickly between emotionally complex inner worlds and a wider, macro perspective. It seemed natural that these graphic narratives should be more commonly produced, but they weren't.

We initially approached a handful of writers who were collecting stories as part of their work – for example, researchers or journalists or film-makers – and putting them together with illustrators. It was meant to be an experimental zine. We felt the project would have more power if we opened it out and invited applications. When we did, we received a number of fleshed out stories, sketches, and storyboards. From there we began the process of selecting works, incubating a few collaborations, holding artists talks to build conversation around the idea of 'non-fiction', and working with contributors on their narratives.

The number of artists exploring graphic narratives has gone up in India of late. How do you see the scene?

The community of creators is growing quickly and attracting people from different disciplines – this book is an example of that. The medium is being used for conventional story-telling, personal catharsis, documentation, education, etc. It is growing into a space where artists can communicate perspectives and narratives that may not find space in the mainstream. Very different from how it was five years ago.

I think this interest is because the medium has the capacity to give an idea life through characters, time and space. The medium also allows for many different kinds of work, since it is primarily about good storytelling and evocative (not necessarily perfect) illustration – this makes it subversive and exciting to work with. I anticipate that we will see many significant chroniclers and commentators emerging from the comics scene – it is fast growing into a space where artists can communicate perspectives and narratives that may not find space in the mainstream.

What about the audience how large and open is it? Are mainstream, MNC mainstream publishers more open to graphic books? How large is the audience and how open?

Graphic narratives have always been a part of mainstream publishers' programme, but today we are seeing a shift in the kinds of narratives on offer in terms of structure, style, theme, etc. For example, there was a time when the visual language of popular comics was driven by text, and today we have popular comics that are entirely silent. This speaks volumes of how the audience for comics has grown and diversified. Independent publishers and self-publishers have played a big role in this – they have been consistently pushing the bar in terms of content through anthologies, in particular. With every anthology that is released, a brand new audience is being created – and that's a wonderful thing to look forward to.

All the essays are in black and white. Why not in colour?

Black and white has been a common option for many creators working in the non-fiction realm, because of its stark and evocative quality. It lends itself well to the theme of the book.

The visual style here is varied but essentially western. Isn't anyone working in Indian styles?

In non-fiction, visual style is about the narrative detail one selects and how it is highlighted to evoke the mood of the story – all the while communicating a specific reality, which is in this case is contemporary India.

Hills & Stones by Nikhila Nanduri uses motifs from Likhai woodcarving in telling the life of Gangaram, a practitioner of the craft based in Uttarakhand. The patterns used evoke a sense of Gangaram's relationship with his work, it made narrative sense to the author to have them as part of the visualisation.

Similarly, other works in the book have followed the logic of the narrative and, in doing so, complicated ideas of what visual style one expects from a particular space. For example, works have used maps ("The Edge of the Map"), photographs ("E-Waste Sutra"), newspaper collage ("DoubleSpeak"), and found historical material ("Whispers of a Wildcat"), and in doing so have drawn directly from the visual landscape and culture of the sub-continent to communicate an urgent and/or immediate relationship with events unfolding there. These have a direct relationship with the visual culture that we live in. Others still are based on first-hand research into character, location, and time – particularly our reportage pieces The Girl Not From Madras and Notes From the Margins.

First Hand, the end notes say, is to be a series - what comes after this?

We're looking at further volumes, and the potential of their being thematic.

No comments:

Post a Comment